Rainbow crossing in San Francisco's Castro district

The US has shaped global LGBT history and culture in many ways. In some states, same-sex marriage and anti-discrimination laws exist, yet LGBT-related violence is not unheard of. So it was with great curiosity that I travelled to the US as a Sayoni representative, one of 19 participants from as many countries participating in an International Visitor Leadership Program exchange.

Our specific programme focused on civic engagement. The group received an overview of the US political system and, through a series of meetings, a better understanding of how its civil society organisations and government agencies advocate for civil and human rights. The journey took me to four states, Washington DC, South Carolina, Utah and California, with a final stop in San Francisco.

History of a movement

Over the course of three weeks, I met many organisations working to achieve the American narrative of equal opportunity and others that pointed out gaps in that same narrative. I saw geographical mobility and individualism in action while talking to random people who had crossed state and national lines to build the life they wanted. It was clear that the American Constitution and democracy was central to their efforts, a stirring, flawed but attractive ideal.

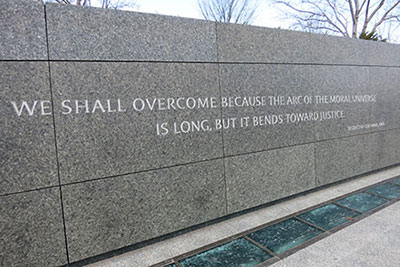

Part of the Martin Luther King Jr memorial

Understanding the historical context of the African American civil rights movement helped me to see its LGBT movement as a natural extension of the struggle for the rights of women and African Americans. Activists have built upon the work of those who came before, whether in harnessing the power of the media or building effective coalitions – Rosa Parks was hardly the first to refuse to give up her seat on a public bus in segregated America, but she was the right person at the right time, supported by the weight of experienced activists. The struggle is also not static, and victories come and go. During our visit, Indiana signed a law to allow businesses to refuse to serve LGBT people in the name of religious freedom. These are lessons that hold true across movements in any country. I was reminded of the short, fraught history of Singapore civil society and that we were still young in many ways.

I also had the opportunity to meet a civil rights icon, Democratic Congressman John Lewis, and passionate grassroots advocates such as Harriet Hancock, who founded a PFLAG chapter in Columbia, South Carolina, for families and friends of LGBT people. It gave me hope to see that the struggle for change shares certain characteristics across national lines, even as our strategies may differ according to context.

Another source of inspiration was the other participants, who are all engaged in meaningful work in their own fields, whether it was helping LGBT people, women, children and other less advantaged groups, or driving political participation in their countries. It is one thing to hear about struggles or oppression in far-off US, Europe or the African region, and quite another to call a distant activist a friend.

Coming home overseas

What I didn’t expect was facing my own issues with national identity and culture. In one of the meetings, I was asked by an academic what my language was. I froze, struck by the irony of hearing the question in an immigrant nation that had also inherited English from its forebears. As a researcher, he was firm that we should begin with an awareness of our own heritage, but there was no easy way to explain what Singlish was. (A creole language, perhaps?)

The national discourse really hit home when founding father Lee Kuan Yew passed away and Singapore mourned en masse. Random strangers in a shop or on a taxi would ask me about him. “I’m sorry to hear about your President,” they said – the title of the head of state varies around the world. Next came the news about Hong Lim Park’s Speakers’ Corner, closed in tribute to Lee, and of the charges against Amos Yee. As I spoke to each person about the nation, I came to understand the mixture of pride and discomfort I and many Singaporeans grapple with.

Outside the programme, I took time out to visit an LGBT centre in Sacramento and a protest in Utah against police mistreatment of a transgender teen from Guatemala, Nicoll Hernandez-Polanco. Apart from wishing that we had a broader range of support services for LGBT individuals in Singapore, I couldn’t fail to see how there was a similar need for awareness surrounding issues of race, sexual orientation and gender identity in both countries.

And that was how I left the US – aware of various facets of the American Dream, both positive and negative, but also with fresh ideas and perspective on my own activism. Perhaps there are some questions that are best asked away from home. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to confront them.